"To give the news impartially, without fear or favor..."

Adolph S. Ochs in his declaration of principles for The New York Times, Aug. 18, 1896

What do you do when you feel like your reputation and business have been hurt by a newspaper story? You could sue the paper for libel and hope the judge or jury rules in your favor.

Things didn't go that way for true-crime author Ann Rule whose 2013 lawsuit against the Seattle Weekly was thrown out last month. A King County Superior Court judge said Rule failed to show that Rick Swart's 2011 article defamed her. The case goes back to July 2013 when Rule said her name and book sales were hurt by Swart's article "Ann Rule's Sloppy Storytelling," which deals with supposed inaccuracies in Rule's book, "Heart Full of Lies." According to the judge, the newspaper was protected by the First Amendment and the plaintiff (Rule) didn't meet the heavy burden of proof showing she was defamed and her reputation sullied. <For more on the case, go here>

While coverage of a lawsuit by a popular American author like Rule may make it seem like libel lawsuits are happening all the time, the number of libel cases against media outlets actually has been dropping since 2010, according to the Media Law Resource Center's 2014 Report on Trials and Damages, which tracks media libel trials. Also of note is that public figures have had less success winning cases against news organizations since 2000, according to Courthouse News Service. Public figures have a more rigorous standard to meet when claiming defamation than private individuals do.

Don't take libel lightly

In one case that seemed to put the press on notice, The Virginian-Pilot (daily circulation 156,968) in Norfolk, Virg., was sued for libel and the plaintiff awarded $3 million in damages. It stemmed from a 2012 suit involving an article that defamed a high school assistant principal. However, in January this year, the Virginia Supreme Court sided with the newspaper, throwing out the libel verdict saying there was no evidence of defamation.

Defending libel cases in court is expensive, as outlined in the 1997 Neiman report, "Has the press lost its nerve?" by James Goodale, a First Amendment lawyer and former general counsel to the New York Times. Goodale was instrumental in the Times' decision to print the Pentagon Papers.

"Libel suits are a fact of life. They should be taken into consideration. But they are not determinative, nor should they chill," Goodale wrote in the Neiman report that goes on to describe several US libel cases that were settled out of court.

Every newsroom, publisher or blogger needs to have a policy on how to handle reader complaints, which may include libel claims. Similarly, a private citizen or public official bringing a case of libel must have solid evidence that meets his or her state's libel laws, as seen in the Virginian-Pilot case. Large media outlets like The New York Times may be able to hire and retain expert legal counsel to sift through potential libel cases making sure they are legitimate before they make it to the editor's desk. But how does a small, independent newspaper protect the words it chooses to publish?

That's the question community paper Whatcom Watch (WW) faces. The monthly pub, which has been in print since 1992, covers environmental and government issues. Last month, Editor Richard Jehn received a letter with the header, "Notice of Libel and Request for Corrective Action." Written by Craig Cole, the letter refers to Sandra Robson's front page January 2014 article: "What Would Corporations Do? Native American Rights and the Gateway Pacific Terminal," and claims the newspaper should print a retraction since the article confuses the reader "as to whether it is fact or a fictionalized hypothetical." In his case for a retraction, Cole mentions another writer, not associated with Whatcom Watch, who had referenced Robson's article in a blog post. "Any implication that I am a racist or anti-tribal is going to trigger serious legal consequences," the letter states.

Things didn't go that way for true-crime author Ann Rule whose 2013 lawsuit against the Seattle Weekly was thrown out last month. A King County Superior Court judge said Rule failed to show that Rick Swart's 2011 article defamed her. The case goes back to July 2013 when Rule said her name and book sales were hurt by Swart's article "Ann Rule's Sloppy Storytelling," which deals with supposed inaccuracies in Rule's book, "Heart Full of Lies." According to the judge, the newspaper was protected by the First Amendment and the plaintiff (Rule) didn't meet the heavy burden of proof showing she was defamed and her reputation sullied. <For more on the case, go here>

While coverage of a lawsuit by a popular American author like Rule may make it seem like libel lawsuits are happening all the time, the number of libel cases against media outlets actually has been dropping since 2010, according to the Media Law Resource Center's 2014 Report on Trials and Damages, which tracks media libel trials. Also of note is that public figures have had less success winning cases against news organizations since 2000, according to Courthouse News Service. Public figures have a more rigorous standard to meet when claiming defamation than private individuals do.

Don't take libel lightly

In one case that seemed to put the press on notice, The Virginian-Pilot (daily circulation 156,968) in Norfolk, Virg., was sued for libel and the plaintiff awarded $3 million in damages. It stemmed from a 2012 suit involving an article that defamed a high school assistant principal. However, in January this year, the Virginia Supreme Court sided with the newspaper, throwing out the libel verdict saying there was no evidence of defamation.

Defending libel cases in court is expensive, as outlined in the 1997 Neiman report, "Has the press lost its nerve?" by James Goodale, a First Amendment lawyer and former general counsel to the New York Times. Goodale was instrumental in the Times' decision to print the Pentagon Papers.

"Libel suits are a fact of life. They should be taken into consideration. But they are not determinative, nor should they chill," Goodale wrote in the Neiman report that goes on to describe several US libel cases that were settled out of court.

Every newsroom, publisher or blogger needs to have a policy on how to handle reader complaints, which may include libel claims. Similarly, a private citizen or public official bringing a case of libel must have solid evidence that meets his or her state's libel laws, as seen in the Virginian-Pilot case. Large media outlets like The New York Times may be able to hire and retain expert legal counsel to sift through potential libel cases making sure they are legitimate before they make it to the editor's desk. But how does a small, independent newspaper protect the words it chooses to publish?

That's the question community paper Whatcom Watch (WW) faces. The monthly pub, which has been in print since 1992, covers environmental and government issues. Last month, Editor Richard Jehn received a letter with the header, "Notice of Libel and Request for Corrective Action." Written by Craig Cole, the letter refers to Sandra Robson's front page January 2014 article: "What Would Corporations Do? Native American Rights and the Gateway Pacific Terminal," and claims the newspaper should print a retraction since the article confuses the reader "as to whether it is fact or a fictionalized hypothetical." In his case for a retraction, Cole mentions another writer, not associated with Whatcom Watch, who had referenced Robson's article in a blog post. "Any implication that I am a racist or anti-tribal is going to trigger serious legal consequences," the letter states.

Click here to read the Whatcom Watch article

"What What Would Corporations Do? Native American Rights and the Gateway Pacific Terminal"

Click here to read Craig Cole's letter to Whatcom Watch

"What What Would Corporations Do? Native American Rights and the Gateway Pacific Terminal"

Click here to read Craig Cole's letter to Whatcom Watch

David & Goliath?

During the time since Whatcom Watch received Cole's letter, John Servais has been publishing articles on his news website "Northwest Citizen" about the situation, and readers have weighed in via online comments. Apparently, some folks are critical of how WW is handling the notice. Others have said the letter is a censorship tactic by SSA Marine, as Cole, the author of the letter, is a consultant for that corporation.

Some background may be helpful here. Whatcom Watch has published articles critical of SSA Marine's proposed deep-water port slated for Cherry Point in Whatcom County. The proposal is controversial as coal is one of the commodities it will import and export. Proponents support it for potential economic benefits. Environmental groups meantime are fighting to stop the port idea, citing negative health and safety consequences the export of coal to China may bring. The scoping process of the project has been completed and now the draft Environmental Impact Statement is being crafted.

As far as Whatcom Watch goes, it's important to mention that I served as editor in 2010-2011, have been a contributing writer and volunteer since 2007, so naturally I support the paper and its mission to provide a community voice. A few week's ago when I learned about Cole's letter, I offered to be a listening ear to anyone from Whatcom Watch and provide some practical advice as a journalist. Because I had the experience of serving as editor -- the unpaid 'all guts, no glory' position that accepts full responsibility for the 2,400-a-month circulation newspaper -- I figured they may want to bounce some ideas around on how to approach such a letter.

I am not an attorney and do not provide legal advice. I am a professional journalist since 1991 and a college professor who teaches newswriting and mass media courses. Also, in my role as volunteer correspondent for Reporters Without Borders and a member of the Freedom of Information committee for the Society of Professional Journalists, it's my job, interest and duty to be fully informed and educated on libel and First Amendment issues. Since 2010, I have been covering press freedom from a global standpoint, studying the media in Iceland and monitoring freedom of information for RWB, which protects journalists worldwide.

During the time since Whatcom Watch received Cole's letter, John Servais has been publishing articles on his news website "Northwest Citizen" about the situation, and readers have weighed in via online comments. Apparently, some folks are critical of how WW is handling the notice. Others have said the letter is a censorship tactic by SSA Marine, as Cole, the author of the letter, is a consultant for that corporation.

Some background may be helpful here. Whatcom Watch has published articles critical of SSA Marine's proposed deep-water port slated for Cherry Point in Whatcom County. The proposal is controversial as coal is one of the commodities it will import and export. Proponents support it for potential economic benefits. Environmental groups meantime are fighting to stop the port idea, citing negative health and safety consequences the export of coal to China may bring. The scoping process of the project has been completed and now the draft Environmental Impact Statement is being crafted.

As far as Whatcom Watch goes, it's important to mention that I served as editor in 2010-2011, have been a contributing writer and volunteer since 2007, so naturally I support the paper and its mission to provide a community voice. A few week's ago when I learned about Cole's letter, I offered to be a listening ear to anyone from Whatcom Watch and provide some practical advice as a journalist. Because I had the experience of serving as editor -- the unpaid 'all guts, no glory' position that accepts full responsibility for the 2,400-a-month circulation newspaper -- I figured they may want to bounce some ideas around on how to approach such a letter.

I am not an attorney and do not provide legal advice. I am a professional journalist since 1991 and a college professor who teaches newswriting and mass media courses. Also, in my role as volunteer correspondent for Reporters Without Borders and a member of the Freedom of Information committee for the Society of Professional Journalists, it's my job, interest and duty to be fully informed and educated on libel and First Amendment issues. Since 2010, I have been covering press freedom from a global standpoint, studying the media in Iceland and monitoring freedom of information for RWB, which protects journalists worldwide.

Practical Steps

With that, I've culled some practical information that is helpful for newsroom editors and for those who find themselves in a position to claim libel. This is not legal advice.

1) What does defamation mean? Defamation is expression that damages a person's reputation. When it occurs in print or publication, it's referred to as libel. When it's spoken, it is considered slander. Keep in mind that defamation on the Internet, including social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, would fall under libel (See "The Law of Public Communication," by Mittleton and Lee).

2) Can an editor go to jail for a libel case? This is unlikely as defamation cases in the US are almost always civil carrying monetary damages, not criminal leading to jail time. (See "The Law of Public Communication," by Mittleton and Lee).

3) State laws differ on libel. In Washington state, anyone claiming libel must meet these four important elements including falsity; an unprivileged communication; fault on the part of the defendant; and damages. More clearly, as the Digital Media Law Project outlines, when someone claims they have been libeled, they need to show the exact words, sentences, passages and language that has harmed them. You can't just have a feeling that an article puts you in a negative light or surmise that someone might interpret a passage a certain way. Also, you need to show that your life has been negatively affected -- inability to land a job, business sales falter, discrimination or emotional harm. Again, the burden of proof weighs heavily on the person making the claim so you must have financial statements or other documents showing you've experienced damages.

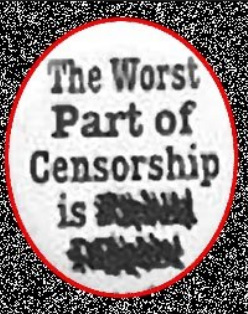

4) Be aware of "Anti-SLAPP laws that help protect speech. "Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation" (SLAPP) are meant to intimidate and silence critics creating a chilling effect among publishers and writers. Thankfully there is anti-SLAPP legislation "to protect people from lawsuits of questionable merit that are often filed to intimidate speakers into refraining from criticizing a person, company, or project. Fighting these suits can be a time-consuming and expensive enterprise," according to the Reporters Committee For Freedom of the Press.

5) Consider a public editor. Readers have the right, and responsibility, to provide feedback to their local newspaper in the form of Letters to the Editor, complaints, observations or even claims of libel. This healthy communication between reader and publisher encourages lively debate in a democracy and keeps the media itself on notice when it fails in its press freedom responsibility. To aid in this dialogue, a public editor, or ombudsperson, can approach issues objectively. Check out Margaret Sullivan, the public editor for the New York Times who explores news coverage from an impartial, or even critical viewpoint, not always siding with the Times' editors on how they handled a story. Fielding complaints can be an unpopular job, but the role is vital to a newsroom's credibility by serving as a watchdog on the watchdog. Read Sullivan's column or find her on Twitter to get the gist of how one public editor handles readers' issues.

To preserve and encourage a vibrant, credible, trustworthy press, editors and writers need to be overly diligent with their tools of the trade -- words. Those who exercise their right to challenge these published works need to meet the highest standards to make a legitimate claim. Otherwise, our press would falter in its duty to publish freely without "fear or favor."

With that, I've culled some practical information that is helpful for newsroom editors and for those who find themselves in a position to claim libel. This is not legal advice.

1) What does defamation mean? Defamation is expression that damages a person's reputation. When it occurs in print or publication, it's referred to as libel. When it's spoken, it is considered slander. Keep in mind that defamation on the Internet, including social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, would fall under libel (See "The Law of Public Communication," by Mittleton and Lee).

2) Can an editor go to jail for a libel case? This is unlikely as defamation cases in the US are almost always civil carrying monetary damages, not criminal leading to jail time. (See "The Law of Public Communication," by Mittleton and Lee).

3) State laws differ on libel. In Washington state, anyone claiming libel must meet these four important elements including falsity; an unprivileged communication; fault on the part of the defendant; and damages. More clearly, as the Digital Media Law Project outlines, when someone claims they have been libeled, they need to show the exact words, sentences, passages and language that has harmed them. You can't just have a feeling that an article puts you in a negative light or surmise that someone might interpret a passage a certain way. Also, you need to show that your life has been negatively affected -- inability to land a job, business sales falter, discrimination or emotional harm. Again, the burden of proof weighs heavily on the person making the claim so you must have financial statements or other documents showing you've experienced damages.

4) Be aware of "Anti-SLAPP laws that help protect speech. "Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation" (SLAPP) are meant to intimidate and silence critics creating a chilling effect among publishers and writers. Thankfully there is anti-SLAPP legislation "to protect people from lawsuits of questionable merit that are often filed to intimidate speakers into refraining from criticizing a person, company, or project. Fighting these suits can be a time-consuming and expensive enterprise," according to the Reporters Committee For Freedom of the Press.

5) Consider a public editor. Readers have the right, and responsibility, to provide feedback to their local newspaper in the form of Letters to the Editor, complaints, observations or even claims of libel. This healthy communication between reader and publisher encourages lively debate in a democracy and keeps the media itself on notice when it fails in its press freedom responsibility. To aid in this dialogue, a public editor, or ombudsperson, can approach issues objectively. Check out Margaret Sullivan, the public editor for the New York Times who explores news coverage from an impartial, or even critical viewpoint, not always siding with the Times' editors on how they handled a story. Fielding complaints can be an unpopular job, but the role is vital to a newsroom's credibility by serving as a watchdog on the watchdog. Read Sullivan's column or find her on Twitter to get the gist of how one public editor handles readers' issues.

To preserve and encourage a vibrant, credible, trustworthy press, editors and writers need to be overly diligent with their tools of the trade -- words. Those who exercise their right to challenge these published works need to meet the highest standards to make a legitimate claim. Otherwise, our press would falter in its duty to publish freely without "fear or favor."

Further reading & resources

- SPJ Legal Defense Fund

- Student Press Law Center

- How to respond to libel complaints (newspapers)

- How to hire a media lawyer

- What newspapers can do to avoid libel

- Can I bring a libel suit against the local newspaper?

- The News Manual: Defamation, what you can do

- Why is the New York Times v. Sullivan case important?