I grab Betsy Lerner's advice to writers when I'm feeling down or blue about my writing.

I grab Betsy Lerner's advice to writers when I'm feeling down or blue about my writing.

What exactly do I resist? Avoid? Battle with? Struggle with?

So I ask myself: Is it fear of failure? Fear of performing? Fear of rejection?

When I write, I see the faces of my audience, as if I’m on stage. I’m ready to utter my lines, but my throat tightens with censorship. Will the performance be as good as the rehearsal?

I write the story in my head, but when I face the page, my mind is blank like a painter’s new canvas. Why does that prospect instill panic, rather than entice like an invitation?

As I sit at my desk toiling over my next draft, judgment enters the room. She takes a seat, clipboard firmly clasped against her chest. She bites the end of a pen, her peering eyes above the bifocals ooze critique. She’s not front row and center shaking her head. Rather, I see her midway, maybe seven or eight rows back, just far enough to give the guise of objectivity, yet close enough that I can feel her heat.

These worries are cliché: a writer stalled, mind numb, paralyzed in the chair, what to write?

Enough of this, I say.

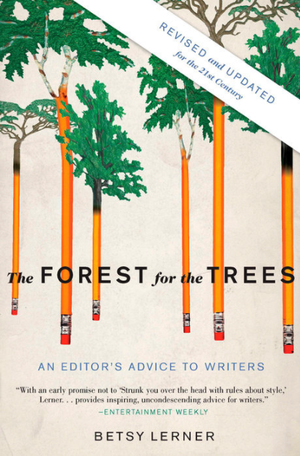

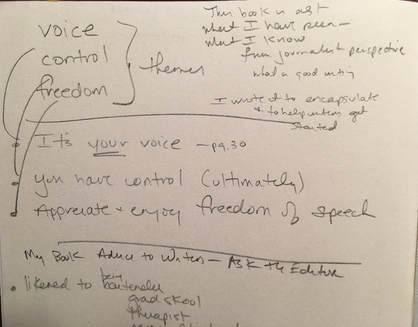

The block begins to melt, just slightly. I pull a marked-up paperback off the shelf. On the cover, I see six thin pencils, standing at attention, serving as tree trunks to the web of ideas a writer calls upon when she grabs words from head and heart. The inside back cover is like a New York City subway car in the 80s: scribbled graffiti with lists, arrows, bullet points -- my notes from the first time I read the book.

As I flip through the pages, I happily find several passages that I had circled, underlined or starred to remind me why I am a writer, why I struggle with my confidence and why I resist my muse.

From Lerner, I learn:

|

“The ambivalent writer is often so preoccupied with greatness, both desiring it and believing that every sentence (s)he commits to paper has to last for eternity, that (s)he can’t get started.”

“Whatever you do, don’t censor yourself. There’s always time and editors for that.” “If you are writing to prove yourself to the world, to quiet the naysayers at last, to your cold and distant father take notice, I say go for it.” “Writing demands that you keep at bay the demons insisting that you are not worthy or that your ideas are idiotic or that your command of the language is insufficient.” “The ambivalent writer confuses procrastination with research." |

To be instructive, Graham had reassembled a series of the student's poems in such a way that transformed Lerner's approach to writing. The poems had gone from “acorns" to "an oak,” Lerner recalls.

Judgment does not have to be front and center; relegate her to the back row.

“If you are struggling with what you should be writing, look at your scraps,” she says.

Back at my desk, I sit down and pull the paper snowballs out of the trash. I dust off an unfinished essay that was demoted to the lower drawer I rarely open.

I hear Lerner's advice continue: “Whatever you do, I beg you not to look at the bestseller lists.”

Don’t try to copy what already exists, she says. Look at your scraps; therein lies your pot of gold.

Now, resist the voices that sit on your shoulder. Judgment does not have to be front and center; relegate her to the back row, I tell myself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed